Jane Wilson-Howarth's first book was published in 1990 - 'Lemurs of the Lost World: exploring the forests and crocodile caves of Madagascar' - and she has published several other books, across genres, since. This quote from her own biography gives you an insight into Jane: while other girls were experimenting with makeup and exploring the impact on the boys of rolling up the waistbands of their skirts to show more leg, I was nerdily nose-down in our garden pond, learning about reproductive behaviour in minuscule cyclops and water-fleas. After graduating with a zoology degree from Plymouth, Jane travelled to Nepal, for the first time. Travel gave me a particular loathing of leeches and parasites, as well as an indignation about inequality of access to health care. Ultimately this pushed me towards becoming medically qualified. I have worked as a GP (family physician) in Cambridgeshire for 15 years and have worked in other medical roles overseas for about 13 years.

I was honoured to be interviewed by my friend and fellow author for her blog.

Author to Author

Shaista Tayabali, do please tell us a little about your new book and who your target audience is.

You have written, ‘I don't write for catharsis. I write to tell the truth of my life.’ What do you mean by this?

Do you keep a diary, Shaista? Is it important for writers to do so?

How long did it take to complete the book and have it in a form you were willing to share with people beyond your family and friends?

Reading your work, it feels like becoming a poet / writer is your raison d’être … Do you think people still make judgements about the quality of your writing according to whether you are ‘properly’ published or not? After all, plenty of rubbish is published by celebrities who can’t write and plenty of excellent work is self-published.

I am a bit of a stickler for ‘correct’ writing and am always pulled up short when I notice a typo or punctuation error in a book produced by conventional publishers. It is hard to pick up typos yet there was not one in your book! Congratulations. How did you manage that? How many readers helped by checking through it?

I was slightly shocked at your observations about the way people imply that even if you have a life-altering illness, doing nothing is still considered unacceptable verging on the sinful. Do you think having a strong work ethic is a good or a bad thing?

You wrote, Shaista, ‘A friend visited and did not like to see the tears in my eyes, the tiredness. I am a river of sadness,’ I sighed.

‘Well you can’t be,’ he said, sternly. ‘There’s no such thing. Rivers move and change and take things away with them and pick things up, like flowers and happiness. Write me a happy poem!’

How do you manage to marshal positivity when you are facing so many challenges?

I was interested that you feel doctors critically judge what symptoms are physical in origin and which due to psychological effects or diagnoses. Do you consider this classification of disease into either physical or mental important?

If I mention I had a child who died, many people react as if they need sympathy because of hearing this sad fact. When you mention your father is blind or your life is dominated by illness, people also seem to be in need of comfort. It is so odd, isn't it! Do you have a way of dealing with such responses?

You mentioned that one of your consultants shared an anecdote about another of his patients. Quite rightly he didn’t identify the patient but you felt it wasn’t the consultant’s right to share the story, even if the patient wasn’t identifiable and he intended the tale to help you? When is it acceptable to share others’ stories? What was it that you didn’t like? Was it that you feared he might betray patient confidentiality regarding you?

You say, ‘Just as the triggers for depression are correct and present every day, so are triggers for joy.’ Can you share any tips for accessing what is joyous in life?

I would imagine that your blog helps others. Do you know who reads your blog and do you have any heart-warming stories of those you have connected with through it? Do please share a link to it.

What global issues are you most passionate about? Do injustices get to you?

Do you have another work in progress?

I first met poet and author Shaista Tayabali when I was invited to speak at a readers group in Cambridgeshire many years ago and we made a connection that has continued. I have been following her inspiring blog since I became aware of it and her patient perspectives have often given me pause for thought in my own medical practise. She has just launched her own memoir and generously agreed to answer some questions about it.

Shaista Tayabali, do please tell us a little about your new book and who your target audience is.

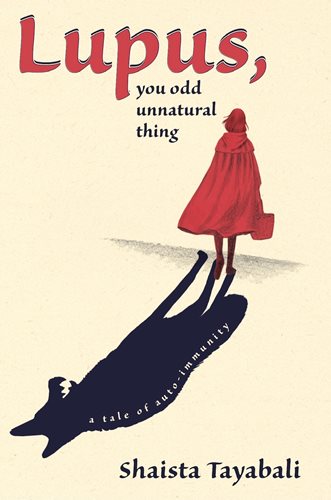

As with any book, a writer’s first audience is herself. In my case, I had returned home from my diagnosis in 1997, googled ‘writers with lupus’ and ‘books written by famous writers with lupus’, searching for something literary, poetic. Over the years, I would check again and again, and nothing of the sort I yearned for, existed. A Kahlil Gibran-ish translation of my life! It dawned on me that I would need to write the book myself, for myself. As I worked through draft after draft, three audiences became clear: the lupus patient, the non-lupus patient and the medic. If I had to pick one in particular, it would be the medic. I was aiming to be on par with Paul Kalanithi, Atul Gawande, Siddharth Mukherji, Oliver Sacks. In other words, I was tired of being the fodder for best-selling doctor-writers!!

You have written, ‘I don't write for catharsis. I write to tell the truth of my life.’ What do you mean by this?

Throughout the writing of this book, people always assumed that my book was intended to ‘help’ lupus patients. ‘This book will really help people like you’ – it was an understandable comment but was neither the genesis nor the ongoing pulling force. I write in the vein of so many women before me, and still writing – like Susan Sontag, Alice Walker, Deborah Levy – but also David Sedaris, Marian Keyes, Samantha Irby – memoirists, essayists – writing for the love of language, through trauma, via poetry or humour. Yes, there is something of transformation in using language as a survival mechanism, but catharsis suggests the thing itself is extinguished. It isn’t. The thing I am writing about – my life – goes on. Thankfully!

Do you keep a diary, Shaista? Is it important for writers to do so?

I don’t keep a diary in the way of David Sedaris, for example – who is religious about it – but I have always kept poetry journals, in which I also periodically record moments in prose. When I started my blog in 2009, that became a diary of sorts. There are gaps in everything – I am not a disciplined, routine based person, but I am always, and always writing – lots of letters, emails. I had the most beloved friend, Mary, who was 60 years older than me. She was a profoundly energetic letter (and later email) writer until the very end – she influenced me endlessly, just by being herself. I think writers find a way to write.

How long did it take to complete the book and have it in a form you were willing to share with people beyond your family and friends?

Well, I started the first line on January 1st, 2013 and published it on December 3rd, 2021! I began it during my Masters in Creative Writing Fiction. I had a novel nicely begun, which my fellow classmates were enthusiastic about, and I swerved. I decided to focus on memoir instead, for my dissertation. So that meant the first draft of my book was not only read but marked. My younger brother was my first reader/critic – and he advised cutting the first quarter, which focused on our life in India – and my older brother was my last proper reader/critic – and he took a similar axe to the draft he read! Along the way, I’d send the book out, and it kept getting rejected by agents. Which would make me go back to it with more scalpels. Until, finally, at the start of this year, I knew it was as right as I could make it.

Reading your work, it feels like becoming a poet / writer is your raison d’être … Do you think people still make judgements about the quality of your writing according to whether you are ‘properly’ published or not? After all, plenty of rubbish is published by celebrities who can’t write and plenty of excellent work is self-published.

‘A hundred percent!’ to quote the young ones… I write it in my early chapter – I was always being asked if I was published, by people who openly said they didn’t even read. Nothing has changed in terms of the legitimacy lent by traditional publishing. The gatekeepers say they aren’t gatekeepers, but they are. And several agents were honest about why they were rejecting me – that it had nothing to do with my writing, and everything to do with the subject matter of my book being unsaleable. My poetry has consistently been rejected too – hence my self-publication via my blog and first collection. It’s tiring to be honest, Jane. Super tiring. Because – and is this arrogant? – I know I can write! (Clive James always thought I was arrogant, but he approved of the arrogance, really – he just wished I’d look up to him more!)

Hear, hear, Shaista! It seems to be that a little arrogance in the correct quarters is what folks need to suceed – in all walks of life. Perhaps calling it self-confidence rather than arrogance would sit easier with you!

I am a bit of a stickler for ‘correct’ writing and am always pulled up short when I notice a typo or punctuation error in a book produced by conventional publishers. It is hard to pick up typos yet there was not one in your book! Congratulations. How did you manage that? How many readers helped by checking through it?

Ha ha! That’s funny, because my younger brother wrote the same thing to me after he finished reading the book. He said he was thinking this throughout his reading. And he says the same thing with my handwritten poetry in my journals. ‘How do you never make a mistake?!’ I do make mistakes, but to answer your question: no readers helped with checking or proof-reading. Only me, over and over and over and over again!! As you know from our own personal connection, I have been editing things for other people for years – since my university days, and probably even at school and sixth form. My consultant calls me his Korrectorin!

I was slightly shocked at your observations about the way people imply that even if you have a life-altering illness, doing nothing is still considered unacceptable verging on the sinful. Do you think having a strong work ethic is a good or a bad thing?

I think those are two very different concepts you are holding there – and it has been interesting to watch the world wrestle with both during this pandemic. People expect to get better when they are ill. They are irritated by anything that stops forward movement. Progress, when you have auto-immunity and chronic illness, looks very different. Progress can be a tiny turn in the late evening, after a horribly stuck day. I have never actually ‘done nothing’ on the inside. I am always busy living, inside. It’s just not very interesting on the outside. I don’t think the ill lack a strong work ethic. And I think placing the words ‘strong work ethic’ beside ‘good’ and ‘bad’ already implies a favourable judgment towards ‘good’? I do work very hard, inside.

You wrote, Shaista, ‘A friend visited and did not like to see the tears in my eyes, the tiredness. I am a river of sadness,’ I sighed.

‘Well you can’t be,’ he said, sternly. ‘There’s no such thing. Rivers move and change and take things away with them and pick things up, like flowers and happiness. Write me a happy poem!’

How do you manage to marshal positivity when you are facing so many challenges?

When I was little, my grandfather told me that my smile made him happy, that me being cheerful made his day better. He was very frail at the time, and I loved him very much. Once feminism really took root alongside serious illness, I took time to examine this business of smiling. Who was I smiling for? Why was I smiling? I stopped for a while. And discovered, slowly, that being cheerful, or perhaps bringing cheer, is an essential part of who I am, regardless of the patriarchy. I don’t think in terms of positive and negative, which, as a former Chemistry student, only remind me of electrons! I know I make a difference with my cheer – it has a visible and palpable effect on the person I am with and on me as well. Living with Dad, who lost his sight almost twenty years ago, also provides a daily exercise in marshalling cheer – cheer is light, translated.

I was interested that you feel doctors critically judge what symptoms are physical in origin and which due to psychological effects or diagnoses. Do you consider this classification of disease into either physical or mental important?

I was sent to a psychiatrist when I was much younger, and I argued my way out as though I were in court. I had no desire to have anyone decide for me what my mind meant. I may have benefitted from that particular doctor, who turned out to be a lovely man, but I knew I wanted my mind for myself. ‘Women with illness’ is a landscape unto itself – we have huge football fields worth of restoration to be done. I was a teenage girl when I entered the NHS and I was treated with incredibly abrasive language. My resultant tears were constantly perplexing, and frustrating to the doctors. As though being diagnosed with a life-threatening disease ought to have no emotional or psychological impact. Mental impact from physical disease is inevitable, just as mental illness plays havoc on the body, eventually, if not immediately. If the two aren’t woven together, your patient falls apart. But modern medicine’s classifications and separated departments don’t allow for a braiding of mind and body. Individual doctors make or break us, according to their levels of compassionate intelligence.

If I mention I had a child who died, many people react as if they need sympathy because of hearing this sad fact. When you mention your father is blind or your life is dominated by illness, people also seem to be in need of comfort. It is so odd, isn't it! Do you have a way of dealing with such responses?

Yes, it’s the conundrum we are constantly faced with: ‘what to say, what not to say’, when you haven’t shared the same human experience. After twenty years, I can usually see a response coming, and employ ninja techniques of getting out of or around the other person’s needs and/or awkwardness. I know my father’s pride, for example, so I simply conjure up a humorous anecdote, one that will spin the conversation onto lighter ground. I am very fortunate that I live with two people who don’t expect anything from me. They hope, but don’t expect. And they are always simpatico. So this makes me able to be generous with others! People who have sympathy for me, rather than expecting sympathy from me, are the ones who become true friends.

You mentioned that one of your consultants shared an anecdote about another of his patients. Quite rightly he didn’t identify the patient but you felt it wasn’t the consultant’s right to share the story, even if the patient wasn’t identifiable and he intended the tale to help you? When is it acceptable to share others’ stories? What was it that you didn’t like? Was it that you feared he might betray patient confidentiality regarding you?

You are referring to a very specific anecdote in the book, during my three-month admission, my most gruelling admission. When the consultant, a man I had only just met during this admission, casually discussed me wearing diapers, because another of his female patients, around my age, had found herself in the unfortunate circumstance of having to resort to them, I found nothing helpful about his offering. It brought me no comfort. As it was, my symptoms cleared up as my inflammatory markers calmed down. His comment was not necessary. I hadn’t asked for practical, sanitary advice. I was just reporting the day’s symptoms during his very brief ward round. His sharing of her circumstance presumed a certain future for me, and that only led to my despair after he left.

You say, ‘Quite rightly he didn’t identify the other patient’ – but here is another situation: as a newly diagnosed teenager, I was desperate for the Rheumatology department to put me in touch with a single other patient. I had never heard of lupus, and I was so lonely, so unhappy. I asked on multiple occasions if my consultant could at least share something concrete about another of his patients, so that I might feel less alone. He never did.

Later, I offered myself to the department, as a point of contact for any newly diagnosed patient – but I was never taken up on it. The confidentiality boundaries that doctors have are not necessarily the ones that we need or appreciate. It’s very complex, isn’t it?

You say, ‘Just as the triggers for depression are correct and present every day, so are triggers for joy.’ Can you share any tips for accessing what is joyous in life?

Well, I can certainly share what is joyous in mine! I am blessed with wonderful friends, who live scattered across the globe. On the occasions when we meet, I draw sustenance from them, but then, in our long absences, I continue to draw on their proffered help, spiritually. On a low, tearful day, I call to mind any one of my family and friends, doctor friends too, and either imagine conversations with them, or sit down to write a letter. In the writing, I am in dialogue, and my friend, far away, busy in their life, is unconsciously bringing me support, energy and ultimately, joy. I say ‘unconsciously’, but when, as a true friend, you offer yourself, ‘I am here for you’, I really take you up on it! Even when you don’t know. I carry the strength and spirit of those who love me, everywhere I go. That’s how I survive hospital and seeming isolation. Bookending my days and nights are my beloved parents. And of course – the children, who are my endless resource of joy – they live in the now, and demand I only be myself, which is easy enough for me, with them.

I would imagine that your blog helps others. Do you know who reads your blog and do you have any heart-warming stories of those you have connected with through it? Do please share a link to it.

One interesting thing about my blog readership, and this perhaps also applies to my book, is that I don’t have an obvious lupus patient following. My readers tend to be writers, artists, poet-thinkers. I do know many of my readers because they have written personally to me, and I have made some extraordinary friends. Many of them found me first – I still can’t believe that I was found by Sherry, who lives in Tofino, Canada or Jeanne-ming, who lives in Chiang Mai, Thailand, or Maggie May in California, or Ruth in Michigan or Terresa in Utah… Sherry and I nearly met a few years ago, when I was supposed to visit my family in Vancouver but I ended up in hospital with an infection the day before the flight. I have met only Terresa and Jeanne-ming in person – and they were wonderful moments. Terresa and I walked the Cambridge cobblestones – I took her to The Haunted Bookshop, off King’s Parade… Ming is a soulmate for sure. We finally met up in Malaysia, the in between place for us – and it was like a coming home. She is an artist of the most unique sort and sent me a piece of art that I absolutely treasure. I came home from an eight-hour monoclonal antibody therapy infusion to find the parcel. I wrote about my soulmate artist friend in my blog, Lupus in Flight: click here to read more radiant joy.

What global issues are you most passionate about? Do injustices get to you?

The safety of women. The rights of our bodies. Our voices. The protection of children, their rights, their voices. Injustice is a living, breathing force every minute of someone’s life, somewhere. When you are very ill, and especially in physical pain, it is unbearable to think that you are a part of the same species who inflict torture upon a body before them. How? I don’t want to know, really. All I know is that at my darkest point, when my eyes were failing me, operations were frequent, a corneal ulcer grew, and all I could think was I belong in the same world as those who commit genocide – the Holocaust and the Rwandan massacre. How do we move beyond that? We are all made of the same stuff. It’s ghastly to think that. And yet… there is light. A friend rang just at my lowest, darkest. He is a man of faith, so his perspective was Christian – Jesus is an embodiment of who we also can be… the news doesn’t allow us to hold on to the necessary threads of light for very long, but we had Desmond Tutu, we have Malala.

Do you have another work in progress?

I have so many books cooking in my head – but specifically my next poetry collection is almost ready, and the novel I began has waited patiently for eight years…

Thanks so much for sharing so much, so succinctly, Shaista Tayabali. Would you also let us have any social media links please?

I think my blog is really my best social media link: Lupus in Flight but I am also on Instagram @shaistatayabali. The memoir is out in paperback and for kindle; here's the link on the UK amazon site: lupus on amazon

It is wonderful to read this interview, Shaista, and i am remembering when i interviewed you at Poets United. I knew you had an amazing spirit, and story.......i am so proud of you for completing this book, which is one of the most memorable books i have read this year. I wish it was required reading for those working in health care. They should call you in to give a sensitivity training workshop.

ReplyDelete